Limiting Reactants

So far, in the reactions we have dealt with, we have assumed that the reactions have automatically gone to completion, that is all of the reactants have been used up in the production of the products. This is not always the case, and very often it can be that there is an insufficient amount of one particular reactant to completely use up another. The reactant which governs the amount of product due to its own (limited) availability is known as the "limiting reactant".

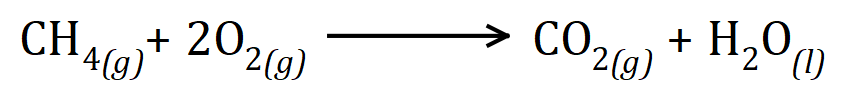

You will see many examples of limiting reactants, such as in the complete and incomplete combustion of natural gas (methane) where sufficient oxygen will cause a complete combustion, and insufficient oxygen (the limiting reactant) leading to incomplete combustion which in the case of natural gas can be dangerous and lead to carbon monoxide poisoning. This is something that we will cover when we reach the organic chemistry section, but it is useful to mention it here to put the calculations we are going to carry out into a real-life context.

An experiment which you will probably conduct many times will involve dissolving magnesium metal into dilute hydrochloric acid to produce a weak solution of magnesium chloride and generation of hydrogen gas. Most of the time you will notice that the magnesium completely disappears because the reaction has gone to completion, since hydrogen chloride (hydrochloric acid) is "in excess" which simply means that there is more of it present than is necessary for the reaction. Hydrocarbons burning in the atmosphere will do so in an excess of oxygen, so for example your gas fire burning methane will combine with the oxygen in the atmosphere to produce carbon dioxide and water. Theoretically there should be no dangerous gases such as carbon monoxide, or carbon (soot) deposits due to incomplete combustion.

In the previous case, magnesium and hydrochloric acid, the reaction comes to an end when the magnesium runs out. It could also be the case that the reaction could stop if we ran out of hydrochloric acid. In this case you would see the "fizzing" stop and evidence of metallic magnesium remaining in your test tube, although it is rarely the case in the school laboratory that we do it this way. The amount of product that is formed is directly proportional to the amount of limiting reactant, so you should be able to see that if we halve the amount of magnesium will produce half of the amount of magnesium chloride and therefore half of the amount of hydrogen gas generated.

Looking at the equation, this is the clean burning of methane in oxygen. We can see that one mole of methane will completely combust with 2 moles of oxygen (diatomic) to produce one mole of gaseous carbon dioxide and 2 moles of liquid water. In molar quantities, 16 g of methane will react with 64 g of oxygen to produce 44 g of carbon dioxide and 36 g of water. You should be able to see that 16+64 = 80 and 44+36 = 80 so the law of conservation of mass is upheld. If we were to increase the amount of methane, but restrict the amount of oxygen to 64 g as we have mentioned, we can only end up with the same amounts of carbon dioxide and water because they simply would not be sufficient oxygen to completely burn the methane, in other words oxygen would become the "limiting reactant". Similarly if we increase the amount of oxygen but kept the amount of methane at 16 g , even if we burn the methane in the atmosphere where oxygen is clearly in excess (as it makes up around 20% of it!) we can still only end up with the same amount of products because the limiting reactant in this case is the methane itself.

>> Questions <<