The Distributive Method

Algebraic Expansions - The Distributive Law

From this law it is easy to show that the result of first adding several numbers and then multiplying the sum by some number is the same as first multiplying each separately by the number and then adding the products.

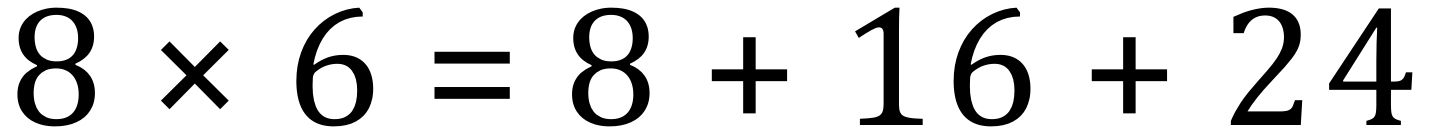

Example:

|

|

|

|

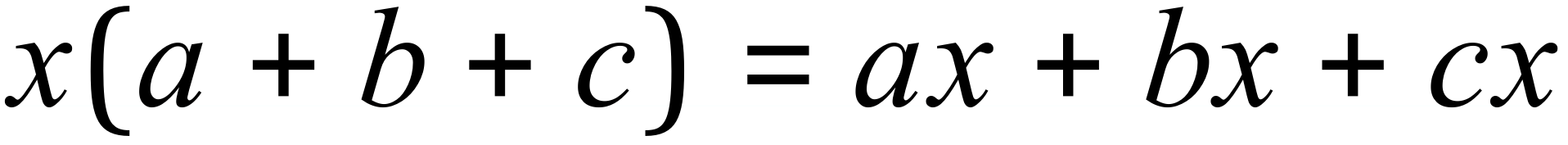

We can apply this law to algebraic expressions involving brackets.

Note that in the example above the “8” was multiplied by the SUM of the numbers “1 + 2 + 3 = 6” to reach the answer “48” but the same answer was reached by making individual multiplications first. The same applies to algebraic expressions:

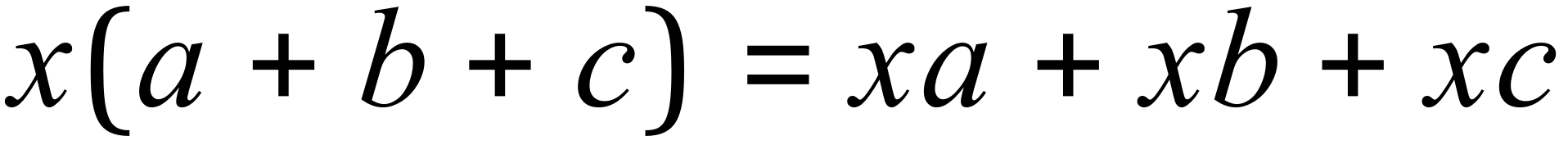

This could have been written as:

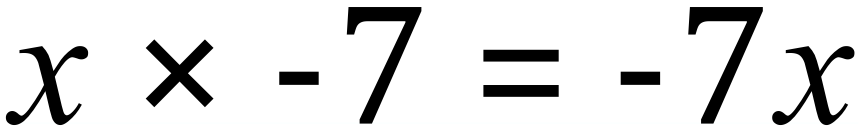

But as multiplication is commutative (can be done either way around, like addition) then:

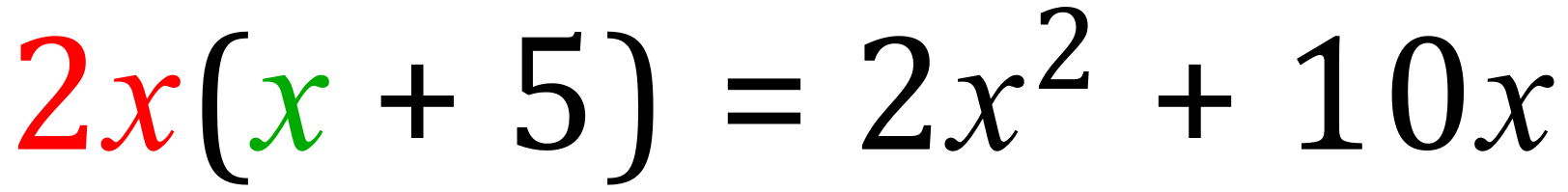

Single Expansions:

Example:

Step 1:

Step 2:

Step 3: put them together

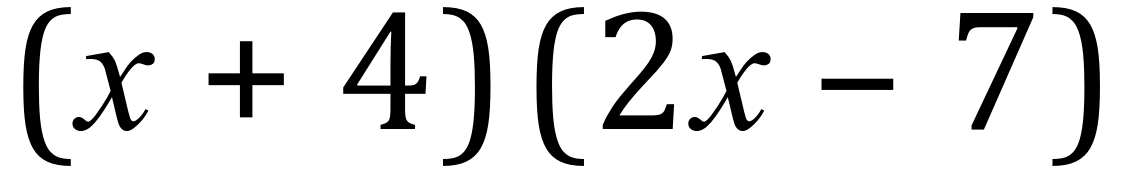

Double Expansions:

In these cases, each entity in one bracket is multiplied by each entity in the other, then the resulting terms are collected and simplified.

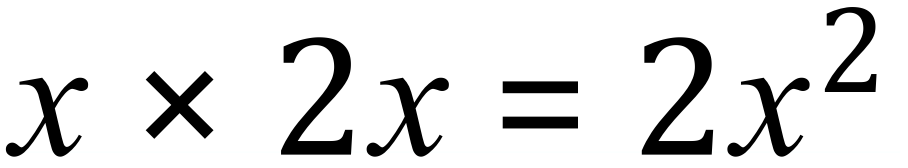

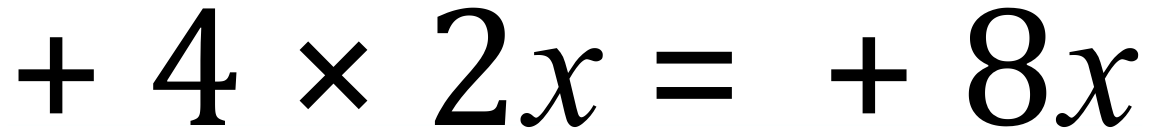

Example:

Step 1:

Step 2:

Step 3:

Step 4:

![]()

Collecting terms:

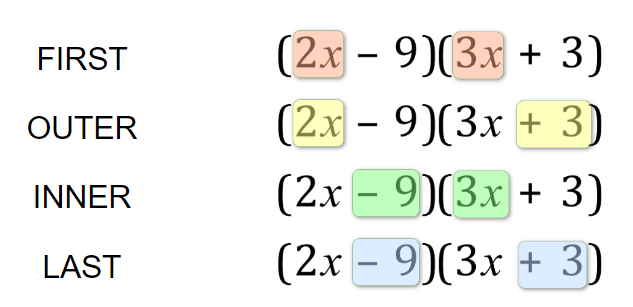

You may have seen this before, called “The FOIL Method” where the “Firsts” “Outers” “Inners” and “Lasts” are multiplied:

Remember that each entity carries a sign, this always goes with it, so for example in the expression above we have:

|

|

|

|

|

Try these:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

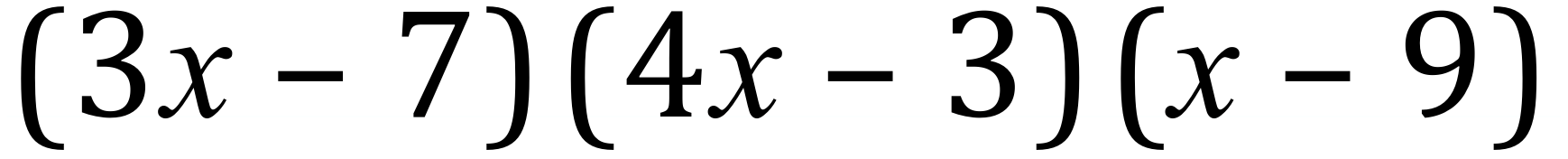

Challenge:

(Hint: multiply any 2 sets of brackets, then multiply the result of that expression by the remaining bracket).

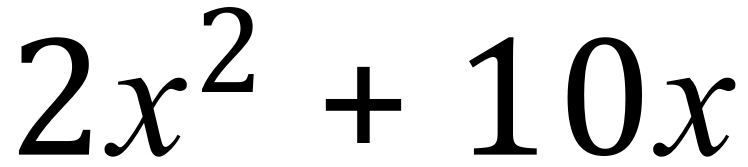

Factoring / Factorisation

This is essentially the ‘reverse’ of Expansion, a little trickier until you get used to it. With Expansion we are taking the ‘factors’ and creating the ‘expression’, in Factorisation we have the expression but have to dig out the factors.

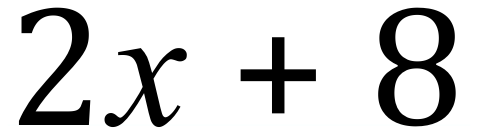

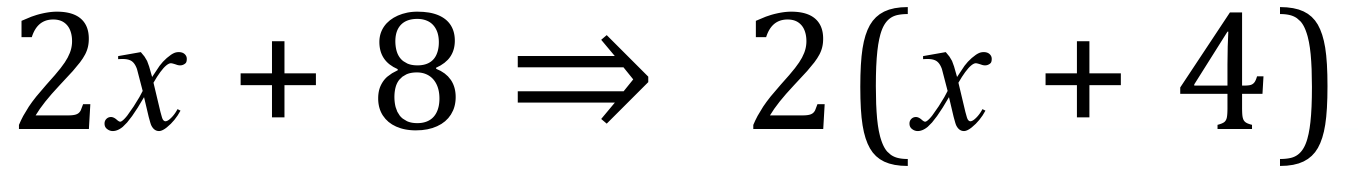

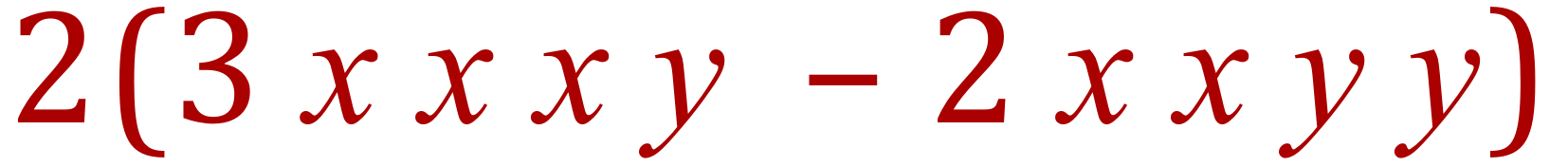

Let’s look at an example:

Step 1 – look for ‘common factors’ in each term of the expression and take them out of the expression, bracket what is left:

2 is a common factor to both 2 and 8, but ‘x’ is only common to the first term so it can’t come out:

Step 2 (optional but advisable) – multiply back out, or ‘expand’ to make sure that you get the original expression back, if you don’t you’ve gone wrong somewhere.

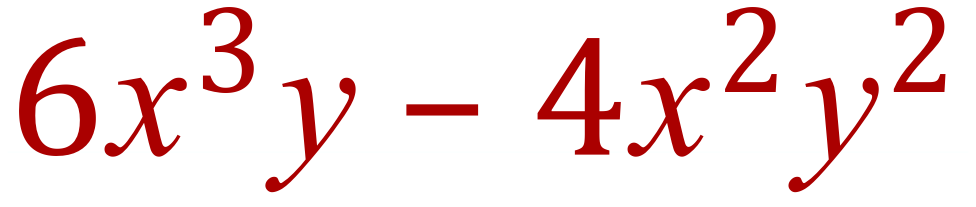

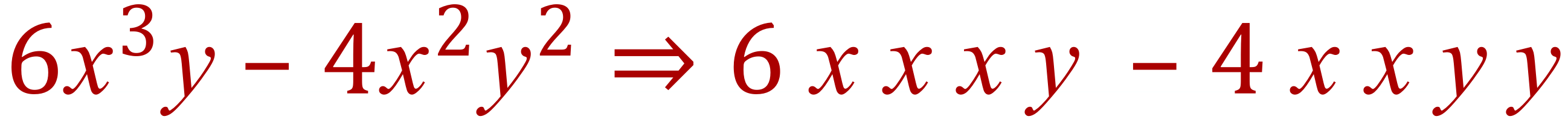

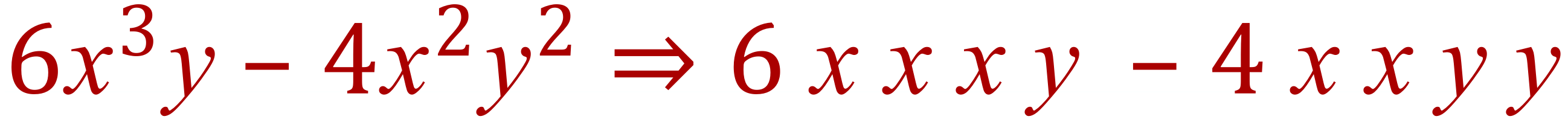

Let’s see another example, a bit harder but I’ll split this into pieces to show how to identify the factors:

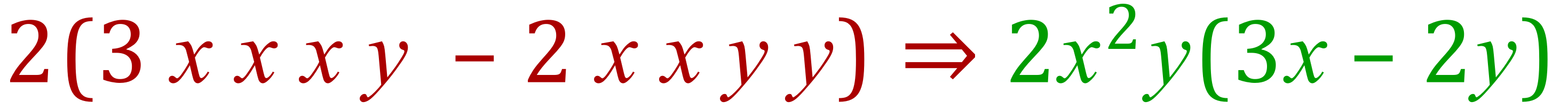

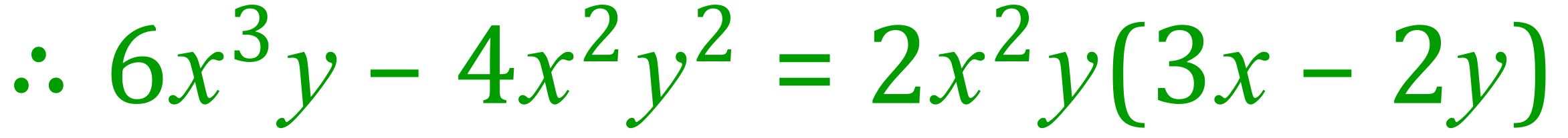

Example 2:

Step 1 – until you are VERY skilled, I’d advise this step.....split the terms into the individual variables:

Step 2 – look for a common factor in the coefficient (the number bit). You may be able to see that 2 is a common factor so we can remove 2, leaving 3 and 2 (think....2(3-2))

Step 3 – look for common factors in the variables:

All of the common variables are sent to join the “2” outside the brackets and regrouped where necessary, this produces.........

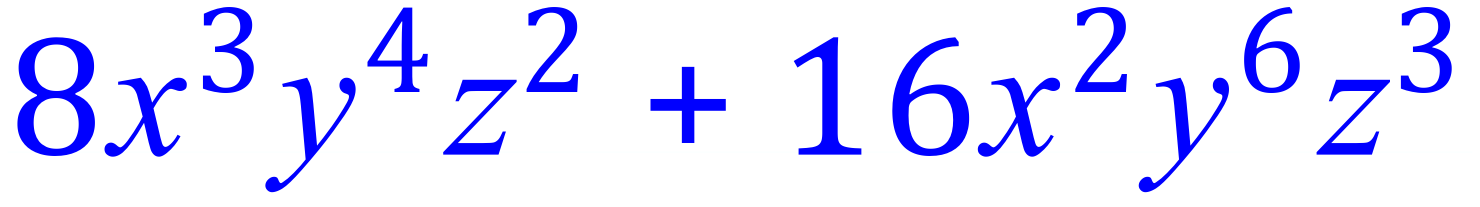

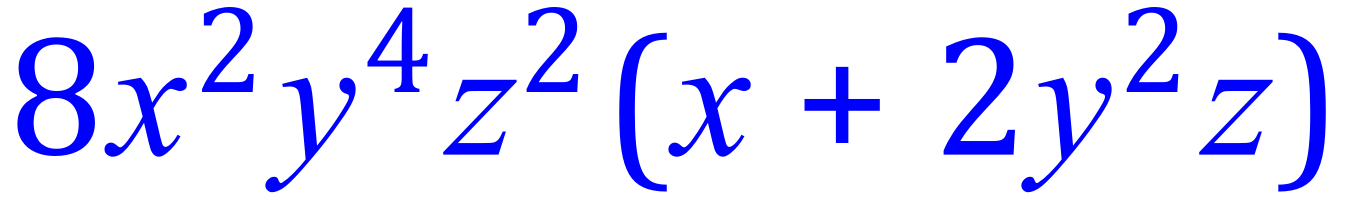

Example 3:

Let’s have a look at one more example, broken apart in the same way:

Step 1 – 8 is a factor of 8 and 16, note that 1, 2, 4 or 8 would have worked but to factorise fully and efficiently we need to find the HCF.....8 in this case:

Step 2 – take the coefficient HCF out:

Note that the “1” isn’t really necessary, I’ve shown it to help you see the factoring involved

Step 3 – take out the common factors in the variables:

Step 4 – recombine the variables and take them outside of the brackets to join the “8”

Ideally the first part of the resulting expression could be further factorised:

So:

These are quite extreme, the sort of example you would see on your test would not be this complicated. If you can follow these though, you will cope with test questions quite comfortably.

>> Questions <<